by Lindsay Cowle

The Saxon monk Alcuin painted this rather romantic view of York and the Ouse in the 8th century:

‘From the most distant lands ships did arrive

And in safe port lay there, tow’d to shore.

Where, after hardships of a toilsome voyage,

The sailor finds a safer retreat from sea.

By flow’ry meads, on each side of its banks,

The Ouse, well stored with fish, runs through the town.’

Whilst the River Ouse and its ‘flow’ry meads’ below York are now primarily a focus of recreation, especially for walkers and boating enthusiasts, it easily forgotten that this is a relatively recent role, and that for most of the last two millennia the river has served as the main access point into York and as a hard-working route for the industry on which York has depended; and that in this previous role it has undergone some major changes.

The tidal River Ouse was critical to the Roman occupation of north Britain, although it may have already adopted that role in pre-historic times. There were Roman quays below Lendal Bridge to serve the colonia and on the Foss to serve the garrison. Among other things the Ouse was a major route for the export of Pennine lead to the Roman Empire, via Boroughbridge, and even up to the 16th century York fought hard to protect its status as the main point of lead export from Yorkshire.

During the Roman occupation the nature of the river was clearly favourable enough to make it navigable by sea-going boats utilising the tides or, more locally, for bringing building stone to York from the Magnesian limestone quarries at Tadcaster, via Cawood. It was also clearly sufficient to allow easy access for Viking longships to raid York in the 9th century; and in 1066 it provided a route for Harold Hardrada to approach York and win the Battle of Fulford, precipitating the events allowing the successful Norman invasion. There is evidence of English resistance from the opposite side of the river (at Middlethorpe) and the possibility that a ford existed across the Ouse at that time, so Nun Ings could well have played a part in the battle.

Little is known of the history of Nun Ings up to this point. Roman ‘occupation debris’ has been found at the higher level, within an old gravel pit, but there is no recorded evidence of the building from which it came: this area, facing eastwards across the river, could have been a desirable site for a villa and Bishopthorpe Road is now increasingly considered to be of Roman origin. The Archbishop of York must have appreciated this location when he started constructing Bishopthorpe Palace as his residence a mile further down the riverside in 1241.

Shortly after the Norman Conquest, in 1130, a Benedictine nunnery was founded in Clementhorpe, which is recorded in the Domesday book as being an extensive trading area to the south west of the city. It may have originated during the Roman occupation and later to have been a Viking settlement, and it had its own quay. The nunnery was sited on the south side of what is now Clementhorpe (the street), and a short stretch of the boundary wall survives; it was described as being surrounded by a village, with orchards, meadows and a staith (quay).

The nunnery normally housed about a dozen nuns and its history is enlivened by periodic scandals (- mostly ‘weaknesses of the flesh’ -) up to its closure by the Dissolution of the Monasteries in 1536. It was the first Post –Conquest religious house for women in Yorkshire and the only Mediaeval nunnery in the vicinity of York until the Bar Convent was founded 1686. It survived off property endowed to it by its founder, Archbishop Thurstan of York, and later endowments of land (mostly farms) which stretched over Yorkshire and as far as Nottinghamshire.

Close to York the nunnery owned land at Middlethorpe which was rented out to the people of York, and which included land bordering the river and running towards the city, and now known as ‘Nun Ings’. Today it is regarded as starting at what is now Manor Farm and finishing opposite the old Terry’s chocolate factory site, with Bishopthorpe Road providing the boundary on the west side. The road runs along the top of a gravel ridge running southwards out of York, placing the Ings on two levels – a raised plateau next to the road and a lower, flat zone of meadow land near the river, with a sloping bank in between.

The lower land has probably suffered from periodic flooding for millennia and so, strictly speaking, this is the part for which the label ‘Ings’ really applies. It is referred to in old documents as ‘Little Ing’ and later ‘Nune Enges’, and in the late 16c a John Clynt was convicted of ‘cutting and carrying away of Ouse bank at the Nunynges side to the great nuisance’. The land above the flood zone was referred to historically as ‘Nonne Fields’, and later ‘Nunfield’, and might have extended as far as the present racecourse.

It is most unlikely that the Clementhorpe nuns or their lay sisters would cultivate the land themselves and it is most likely that, like most of their property, it merely yielded rents. Apart from the lower meadow the land was ploughed on a ‘ridge and furrow’ basis – a method which started in the immediate post-Roman period and was common until the 16th century – and the distinctive pattern can still be seen clearly on aerial photographs. Early Ordnance Survey maps label them fittingly as the ‘hilly fields’.

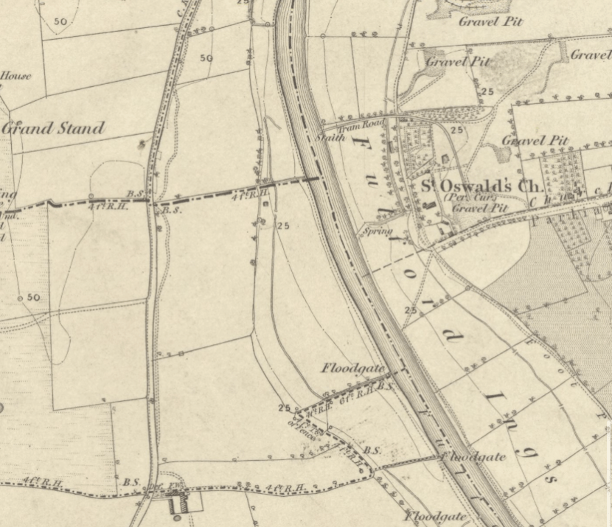

But the nuns may have also benefitted from the grinding of any cereals which were produced, receiving income from two windmills which they owned in the area – one on Scarcroft Hill and the other on Bishopthorpe Road, on the site now occupied by Southlands Chapel (- and which is still shown and labelled ‘Nun Windmill’ on the 1853 Ordnance Survey Map).

The Ouse and its tributaries continued to be the main commercial highways for north and west Yorkshire until the arrival of the railways in the 19th century. In mediaeval times the Ouse had the status of a highway belonging to the King, and there were strict penalties for obstructing it or for unauthorised fishing. In the 17th and 18th centuries the Merchant Adventurers had 100 vessels for transporting exports from York, in particular cloth; stone and timber continued to be imported, as well as coal, woad and mustard seed. In the early 20th century the river was still being used to import sugar cane and cocoa for the new chocolate factories, and even up to the 1990s Scandinavian newsprint was being barged up the river to supply the York Press and grain for Leethams flour mill.

However, river transport seems to have been plagued throughout history by the tendency of the Ouse to silt up, whilst the size of vessels was also increasing. In the mid 16th century the first attempts were made to dredge the river to keep it clear, through fear that York was losing trade to Selby because of it, and by the 18th century it was often necessary to tow vessels up from Selby by horsepower from towpaths on the banks. In 1757 a lock was therefore created at Naburn to increase the depth of water nearing the city.

York’s problems continued to mount up during the 19th century due to competition firstly from steam-powered vessels and then the railways, and the threats from the rapidly expanding cities of the West Riding. The height of Naburn lock was raised in 1835, and again in 1876, and a longer lock was added in 1888 to take steam-powered ocean-going ships.

Essential improvements were carried out to the section between Naburn and York, including dredging, sloping the banks and widening the tow paths in the most needy places. Improvements to the banks may have included narrowing the river – a strategy used to speed up the water flow and counteract silting, and which may have been adopted even during the Roman occupation.

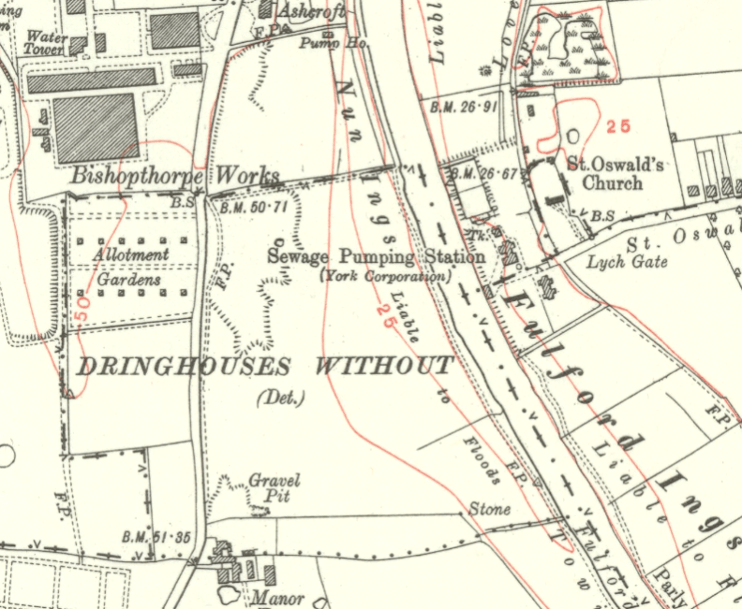

It is not known how all these ‘improvements’ might have affected Nun Ings specifically but the raised towpath along the bank of Nun Ings shown on the first 1853 Ordnance Survey Map (and still existing today) may take much of its form from this campaign. Floodgates allowed field drains to drain to the river under the towpath but with floodgates to prevent ‘backing up’ when the river level was high. The towpath, here on the west bank, was part of a chain of towpaths stretching down below Selby and changing from bank to bank depending on obstacles and the meandering course which the Ouse chose to take.

Cultivation of the Ings must have ceased at some point – probably by the 17th century – and the land reverted to pasture divided up by hedgerows. The historic maps from the 1850s are much more helpful in showing any changes thereafter. By 1907 the upper levels alongside Bishopthorpe Road were being extensively excavated for gravel, which must have been exported by road or possibly by the river to meet the demands of a fast growing city. This was one of many gravel pits spread over the land on both sides of the Ouse, many being much larger (eg those at Middlethorpe and Fulford) with rail and tramways taking material to wharfs on the riverbank. Only a small and perhaps later gravel pit still survives, long abandoned, in the sloping bank at the north end of the site.

The towpath is still labelled as such on maps until the Second World War; but by the late 19th century much of the river traffic had already switched to steam or diesel power, to the extent that at least one Archbishop complained of the smoke nuisance from the river at Bishopthorpe Palace.

The Bonding Warehouse was built in York in 1873 to try to revitalise the city as a port but by then it seems that the city was in both senses ‘swimming against the tide’. The city acquired a dredger and steam tug in 1879, to help tow boats up the river, and had 4 tugs by 1905, but the decline of the city as a port was by then inevitable. Finally, the arrival of the Terrys chocolate factory just to the northwest in 1924 changed the setting of Nun Ings and produced the present intriguing contrast between sublime rural and (in its day) pioneering modern industry.

When the Terrys factory closed in 2005 it owned not only the factory site but a large part of Nun Ings – namely, all the land running down to Manor Farm, but excluding the flat water meadows next to the river. It is not known how or why this land was acquired – factory expansion is most unlikely bearing in mind the nature of the land. Was it bought by Terrys in order to protect the rural setting of the factory, or as a public amenity? Like the rest of the Ings it is still rented out for grazing.

Despite the contrasting backdrop of the Terrys factory Nun Ings is now a place of pastoral peace and calm much enjoyed as a recreation space and for its wildlife, and boating enthusiasts appreciate this tranquil waterborne approach to the city, which retains its rural feel past Rowntree Park , and suddenly enters the busy heart of the city; but it is worth reflecting on the historic events which have shaped this character.

Lindsay Cowle April 2023